Remember the First Brash Black Athlete in Modern Times

Dizzy Dean, the St Louis Cardinals' legendary and colorful pitcher -- and the last National Leaguer to win 30 games in a season -- said it best:

"It ain't bragging if you can back it up."

No one in the history of sports did that better than Muhammad Ali.

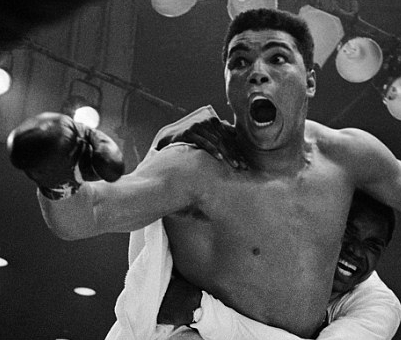

As Cassius Clay, he introduced himself to the world by winning Olympic gold in 1960 as a heavyweight boxer. After stunning the seemingly invincible Sonny Liston four years later to claim the heavyweight crown as a pro, he transfixed it, during and after:

In an era where television was bringing unvarnished news to the masses, no one had ever seen a sports star like this. And in an era where button-down America didn't know what to make of strikes against the establishment -- such as anti-Viet Nam protests and the civil rights movement -- Clay was positioned as just another troublemaker.

To compound matters, the champ announced he had joined the radical Nation of Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. It was just too much for some quarters; Ali had become a villain simply by being himself.

And in Ali's case, it almost put him in prison. Apparently, a high-profile non-Christian couldn't be a conscientious objector to the Viet Nam war and thus be waived from the draft, no matter how well he could express his beliefs:

Consider the irony. At the time, America's elite claimed to be fighting the Communist menace, a system that was painted as subjugating individualism for the good of the state.

Consider the hypocrisy. Much of the media -- sports journalists included -- seek out stories that feature individualism. And yet, when one arises, the reaction is usually one of indignation. No wonder athletes these days stick to a script of harmless, predictable comments so as not to raise the ire of the politically correct.

Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman will never achieve the status of Muhammad Ali, but he is just as entitled to his comments and opinions. The media has mercifully allowed him that, but in this era of sudden news, legions of outlets haven't allowed much thought or research into them.

One reporter who did, Tommy Tomlinson, submitted the sort of reflective review of Sherman's infamous interview with Erin Andrews that one should expect from a responsible journalist. He analyzed the perspective of that moment immediately after Sherman's bat-down of Colin Capernick's pass allowed teammate Malcolm Smith to intercept it and send the Seahawks to the Super Bowl.

Of the 22 thoughts Tomlinson listed in Forbes, here are two of the most pertinent:

- If you stick a microphone in a football player’s face seconds after he made a huge play to send his team to the Super Bowl, you shouldn’t be surprised if he’s a little amped up. [*Note: In this vein, it's no surprise Sherman's interview looked notably similar to Ali's after the 1964 knockout of Liston.]

- But we — the media, and fans in general — don’t know what we want. We rip athletes for giving us boring quotes. But if they say what they actually feel, we rip them for spouting off or showing a lack of class.

Furthermore, the context of Sherman's comments were virtually ignored until later. To wit:

And how long did it take to uncover a previous clash between Sherman and Crabtree?

The media -- sports journalists included -- are entitled to their opinions, too. However, as media, competent reporters have a responsibility to do their jobs by providing an accurate account of events first, so readers and viewers can make up their own minds.

But Sherman's image is cast. His observation that Peyton Manning throws "ducks" amidst a complimentary assessment of the Denver quarterback's game was affirmed not only by Manning himself, but by Bronco receivers such as Demaryius Thomas, who remarked that those wobblers are ''like catching tissue paper.'' And yet, because this is a Sherman comment about an all-but-sainted NFL icon, it's enhanced his villainy.

Fifty years after Muhammad Ali shined a harsh light on media hypocrisy, not much has changed. And with the shallowness of today's shoot-from-the-hip, 24/7 media cycle, it won't.